A (Subway) Desert on the Water

Over the past few weeks, we've discussed how new buildings in New York City come to fruition. We've covered affordable housing mandates, building code regulations, and equity-minded proposals to build a better New York for New Yorkers. This week, we'll pivot from the how to the where. It shouldn't come as a surprise that there's a shortage of space in New York City. New studies show that the densest neighborhoods — with skyscrapers, subways, and full sidewalks — are sinking under their own weight.

Developers must get creative with little space to accommodate the newest condo towers or mixed-use projects. To secure enough space, they sometimes need to push the boundaries of desirability beyond a dozen or so neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Developers invest in ritzy units and lush amenities to coax well-paying tenants further away from city centers and the amenities available in higher-density areas.

The developers take a bit of a gamble — they hope community amenities will pop up as the project draws attention to the neighborhood. As they dream of charging $3,500 for a unit the size of a pinhead, visions of Soul Cycles and Trader Joe's dance in their heads. However, developers cannot build or wish one crucial amenity into existence — transit access.

The public transit system is the lifeblood of New York City — over half of city households do not own a car. The subway plays a crucial role for commuters, students, and even tourists — they can rapidly and economically travel across a region notorious for traffic congestion and inconsistent travel times. It frees city residents from car payments, pricey insurance, and, for some, $500 for monthly parking. But, residents in subway deserts don't always get those benefits.

According to experts, areas further than 0.5 miles from a station fall within a "subway desert" — about a ten-minute walk. That area is confined to slivers along the Hudson and East Rivers in Manhattan. However, most subway deserts lie within the outer boroughs. Red Hook, Sheepshead Bay, and East Flatbush in Brooklyn sit outside the 0.5-mile zone. Most Throgs Neck and Belmont residents in the Bronx cannot easily access the subway. Nearly all Queens residents outside Flushing, Kew Gardens, and Forest Hills are in the same boat.

So much for “rapid” transit…

Photo Courtesy of the

New York Times

Looking at the map, it is no surprise that developers sometimes find themselves away from subway hubs. Massive swaths of land across the city happen to sit within subway deserts. When space is at a premium, the developers can't be picky. Since the early 2000s, luxury developments have increasingly strayed from established neighborhoods in favor of a blank canvas. Riverside South, Hudson Yards, and Long Island City all popped up in inaccessible and previously "remote" portions of the city.

Ocean Drive

Photo Courtesy of the

Red Apple Group

For example, supermarket magnate and political mega-donor John Catsamatidis paid $33 million for two parcels of land about a mile west of the Coney Island Boardwalk in 2011. The project, known as Ocean Drive, proposed a luxury apartment building with a 50-foot pool, a 25,000-square-foot sundeck, and 425 units — 95% boast ocean views. Over a decade later, the New York Times interviewed Catsimatidis on a balcony overlooking the completed Ocean Drive development. The development, over a mile from the closest subway station, offers a free shuttle service for residents. The low-income residents of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) complex down the block must walk or wait for city buses.

Catsamatidis on Ocean Drive

Photo Courtesy of the

New York Times

At Ocean Drive, rents range from $2,500 for a studio to more than $5,000 for a three-bedroom. Since Catsimatidis did not seek out tax breaks from 421a and did not rezone the property, he did not need to add affordable housing. When asked about the project's target demographic, Catsimatidis responded that he welcomes "Whoever is doing well in business and wants to live on the ocean."

However, the luxe amenities and high prices at Ocean Drive mark a significant turning point in subway inaccessible development. Before Catsimatidis built his new megaproject, most residential buildings along the Coney Island waterfront were apartment complexes administered by NYCHA. Most residents around Ocean Drive earn less than the average New Yorker.

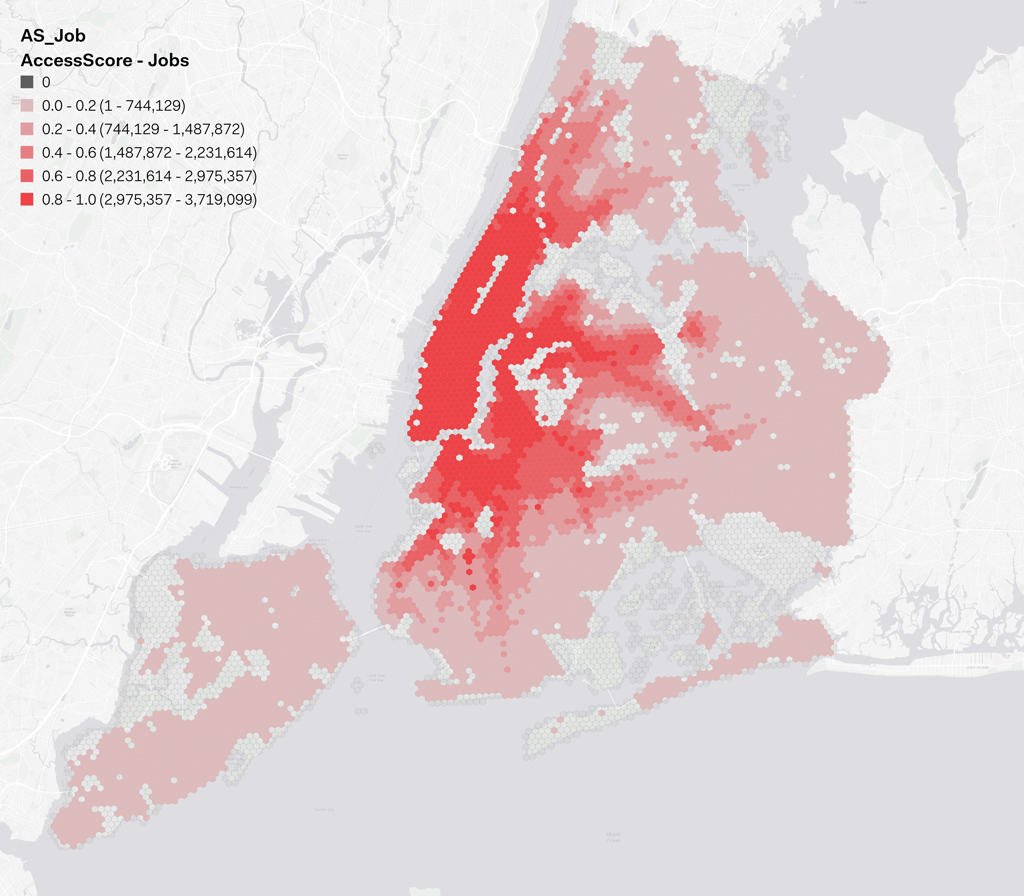

Given New York City's dependence on public transit, individuals will pay premiums to live near subways. Apartment buildings within a tenth of a mile from the subway can charge 8% more than further options. While high earners can often commute easily, lower-income individuals often live far from transit. Let's take a look at the subway desert map again.

The deficits of Ocean Drive on full display…

Photo Courtesy of the

New York Times

Let's focus on a map showing the city's highest- and lowest-income neighborhoods.

Do you see any relationship between income and transit access?

Photo Courtesy of

Transform Transport

See any similarities? You should — many low-income individuals cannot afford to live near a subway station. Without access to public transit or funds for a car, lower-income New Yorkers can access a fraction of the job opportunities as individuals in higher-income, transit-dense neighborhoods.

Access to work = Achieving Goals

Photo Courtesy of

Transform Transport

So, where do we go from here? The answer depends on who you ask. Officials frequently propose bus service extensions to provide subway access to neighborhoods without subways. However, the proposals won't help much given the morning-heavy schedules and slow average speeds synonymous with the city bus system.

Unsurprisingly, subway extensions prove harder and rarer than adding a couple of bus stops. In 2019, officials proposed extending the R train to Red Hook in South Brooklyn. The plan, which includes affordable housing, intends to equitize Red Hook, not the entire transit system. The proposals could provide affordable, transit-accessible homes to a few thousand, not the millions without adequate access to transit.

Many advocates argue that the city shouldn't build new subways. We'd need to utilize the few dozen commuter rail stations across the city. In Melrose and Tremont in the Bronx, many residents can't access a subway. However, each of those neighborhoods connects to MetroNorth. The city plans to add four more in the Eastern Bronx, far from subway stations.

So, problem solved? Transit access is transit access, right? Unfortunately, no. The MetroNorth and Long Island Railroad cost more than three times more than a subway fare — $2.90 to $9.50. Although programs like CityTicket aim to lower the price of Long Island Railroad trips within New York City, the prices still don't match a much cheaper subway trip. And remember, these solutions need to bring subways to low-income neighborhoods. High fares won't accomplish much.

We could mitigate the problem with expanded bus service and bus lanes, discounted ticket costs for intra-city commuter rail trips, and new subways in underserved neighborhoods. However, the local leaders need to reexamine the relationship between transit access and income inequality to fulfill the city's true potential.

Keeping with the pattern, our “Hit and Miss” of the week will focus on transit accessibility.

World Class at the World Trade!

Photo Courtesy of

Davis Brody Bond

Our “Hit” of this week is a part of the ongoing World Trade Center redevelopment in lower Manhattan. Five World Trade Center, a 900-foot tall skyscraper, will house office space, public amenities, and 1,200 apartments. 400 will be affordable, and 20% of those units will be set aside for 9/11 survivors, first responders, and victims’ families. Construction will start in 2024 and wrap up by 2029. Not to mention, it’s on top of a transit hub!

It’d be quicker to canoe to work…

Photo Courtesy of

Progressive Management

Our “Miss” brings us to East New York in Brooklyn. Fountain Seaview 6 is a new affordable housing development along Jamaica Bay developed by the Arker Companies in 2020. It includes 354 units that low-income families receive through a lottery system. Only problem? It’s about two miles from the closest subway station.